Matthew Crawford’s book The World Beyond Your Head (Affiliate Link) is the most important book I’ve read in quite some time.

It makes a sweeping argument about what it means to be an ethical, autonomous human in the digital age.

Crawford draws a strong connection from the distractions buzzing on our phones, to the evolving nature of attention, to how that influences the kinds of individuals we become, to the kind of society such individuals inhabit.

I want to get as many eyeballs on Crawford’s ideas as I can, so I’ve summarized it below as a free post.

Assume anything below is either paraphrased or taken directly from the book.

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction

Our understanding of the self and how it is formed was born at a particular historical moment: the Enlightenment, in 18th century Europe. The memory of centuries of religious wars was fresh, and the project of Enlightenment thinkers was to liberate the individual from every source of tyranny — from rigid tradition, religious dogma, and repressive authorities.

This thinking paved the way for “liberalism,” from the Latin word liber, which means “to free.” By any measure, it’s been one of the most successful projects of all time, giving us precious rights and freedoms and completely reshaping our conception of what it means to be human.

But there has been a cost to this freedom. In order to secure us against any coercive influence, these philosophers placed the ideal self in a vacuum. Removing or weakening the structures that repressed us —social hierarchy, the nuclear family, paternalism, the Protestant work ethic, sexual mores— they also undermined the meaning and coherence that these very same structures once gave our lives.

Companies have stepped into this vacuum to shape our outlook on the world, and therefore our behavior, in their favor. Armed with big data, targeted advertising, real-time notifications, and detailed psychographic profiles, they’ve launched a campaign of distraction to influence what we pay attention to. And what we pay attention to determines our identity.

The conception we inherited from the Enlightenment of what it means to be free is to be free to satisfy one’s preferences. To buy what I want. To consume what I want. To live how I want. We believe these preferences to express the authentic core of our deepest self, a pure flashing forth of the unconditioned will. This self is “free” when there remain no restrictions, encumbrances, or limits on its preference-satisfying behavior. Both the left and the right of the political spectrum are in full agreement on this point: everything can be justified in the name of “giving people what they want.”

But after several hundred years, during which nearly everything about how society works has undergone a radical transformation, how does this idea of freedom hold up?

As radically autonomous individuals, now responsible for choosing every aspect of our identity, we often find ourselves lost in a fog of choices. In a culture predicated on freedom, we are left with the daunting responsibility of constructing a self in the absence of the structures our species has always relied on. Without any established sources of authority guiding us in who or what to pay attention to, our mental lives become shapeless and unmoored. This leaves us highly susceptible to whatever happens to attract our attention — to distraction.

The preferences that we hold so dear are no longer pure, unfiltered urges arising from our deepest selves. They are instead the object of intense social engineering predicated on maximizing distraction. The ecologies of attention that we inhabit — the websites, ads, apps, notifications, and devices — are designed explicitly to hook every perceptual trigger we know of, as often as possible.

Thus our highly individualistic understanding of freedom, inherited from the liberal tradition, leaves us vulnerable to anyone who knows how to use these tools. The paradoxical result of leaving the individual alone in splendid independence, is to deny them the ability to make sense of themselves, others, and the world they inhabit.

The self is left totally free, and totally alone. By removing the will to a separate realm, we were cut off from being able to impact the outside world. The fantasy of autonomy comes at the price of impotence.

Crawford suggests a possible way out of this predicament: skilled practices. In his previous book, Shop Class as Soulcraft (Affiliate Link), he discussed the de-skilling of everyday life. We are no longer expected to have any particular knowledge or skill — just a generalized, abstract form of intelligence suited to solving “general” problems. The ideal of skill has been replaced with the ideal of flexibility, which requires remaining unattached to any particular community, craft, or tradition.

The punch line of that book is that genuine agency is not about being able to make any choice you want (as in shopping). It lies in voluntary submission to things that have their own intractable ways (like musical instruments, gardens, or building a bridge). In order to gain autonomy, paradoxically, you have to start by submitting to a reality beyond your own head.

A new understanding of the individual needs to be grounded in 3 discoveries we’ve made about how the human mind works: that we are fundamentally embodied, social, and situated.

We are embodied

The last couple decades of research in cognitive science have revealed how deeply embodied our minds are.

We don’t gather data about the external world, create an internal model of that world in our minds, and then manipulate the model to determine the proper course of action. Instead, we act on the world, and discover courses of action directly in the medium of physical reality. As the famous saying goes, “the world is its own best model.”

A quick example: when catching a fly ball, we don’t calculate the parabolic trajectories of the ball, and then map probabilistic projections onto a mental model of the field we are playing on, while at the same time calculating wind speed and direction and the friction of our shoes on the grass. Instead, research has found that we simply run in such a way that the ball appears to move in a straight line in our vision. Much simpler, isn’t it?

What this is pointing to is that our basic mode of thinking is extended cognition. We naturally and automatically structure our environment, physically and informationally, in such a way that our reasoning is “dissipated” into the surrounding substrates. It’s quite remarkable really: we are designed to purposefully entangle our minds in complex linguistic, social, political, and institutional webs. This is evolution’s way of reducing the load on our brains, while also gaining access to much greater capabilities.

A simple example: when a bartender receives several orders, the first thing he’ll do is lay out the correct glasses, close together and in a certain order. This trivial action accomplishes two major things: it offloads the remembering of orders onto a physical arrangement of objects, and it facilitates the action of pouring the same fluid into multiple glasses, while reducing spillage.

These “jigs,” or guiding mechanisms, are found in any type of expertise. Our most sophisticated abilities are “scaffolded” by external props — technologies and cultural practices alike — in such a way that they become integral parts of our cognitive system. Andy Clark’s book Supersizing the Mind details how there is no clear boundary we can draw between “native” and “extended” cognition. It’s all us.

Thus the process of developing expertise is not passive accumulation of bits of knowledge. It is running up against the hard constraints of reality. It is contending with the basic relationship of our selves to the world: that it resists our will. As we become skilled, the very elements of that world that were initially sources of frustration, become elements of a self that has expanded.

But there is a way in which modern liberalism interferes in the process described above: it inserts representations between ourselves and the world.

Consider how a baby learns about the world. It pokes and it prods and it drops things and puts things in its mouth. The sensorimotor streams being generated by these actions are bound together into a common experience of time. All the senses co-occurring together in a shared timeline is what allows the baby to improve the effectiveness of its actions. This “cross-modal binding” is believed to be key to our grasp of reality, helping our brain decide that this is not a dream or hallucination.

Now consider how the modern world works: we interact with it through representations.

Driving a late-model car, all the hard edges are smoothed out and padded for us. Comfy seats, power steering, proximity warnings, and now, even driving itself taken care of for us. Separated from the reality of our driving environment, we pay less attention and driving actually becomes more dangerous. Research has shown that narrower roads with less visibility, and without curbs, center lines, guardrails, and even traffic signs and signals, are home to significantly fewer crashes and traffic fatalities. They force people to pay attention.

The use of smartphones is perhaps a more familiar example. Staring into the rectangular screen from a few inches away, we collapse the normal zone of relevance, centered on the body, that normally helps us take our bearings and get oriented. The horizon of near-me and far-from-me gives way to a vague sense of being no place in particular, at no particular time. To be present with those I share my life with is just one option among many. And usually not the most amusing one.

What is constructed is a fragile self. One that is held hostage by the representations through which it interacts with others and reality. This fragile self is eager to take advantage of manufactured experiences, to escape from the frustrations of a world that lacks a basic intelligibility. Gambling and addiction are the classic options. But technology is the ultimate escape, replacing risky uncertainty with a well-structured “choice architecture” installed on our behalf by anonymous designers.

What begins to happen is that we relocate the standard of truth from outside our heads to inside our heads. The worthiness of something in reality is not independent of us, but depends on the representation of it we create in our minds. Basically, how we feel about it.

The problem with this relocation is that attention gets demoted. Or at least redirected. Instead of being a spotlight that illuminates the outer world, it becomes a tool for evaluating our own mental processes. And these processes are supposed to be neutral, detached, objective, not “infected” by our mental biases, and especially not by the opinions of other people. Somehow we evolved from questioning the legitimacy of particular political authorities in 17th-century Europe, to questioning the legitimacy of other people’s authority, to questioning the legitimacy of our own experience.

The incredible discoveries of the last few decades in embodied perception and extended cognition have been resisted at every step. But not because there is no evidence. They’ve been resisted because they contradict the fundamental understanding of the individual on which modern epistemology, the liberal arts, and our whole moral-political order is based.

We are social

The prevailing, Cartesian view of reason is that being rational requires freeing your mind from any taint of outside authority. Kant writes:

Enlightenment is “man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity… [This immaturity consists not in a] lack of understanding, but lack of resolution and courage to use [one’s own understanding] without the guidance of another.” Further, “laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large portion of men … remain immature for life.”

Everything located outside your head, especially other people, are identified as potential threats to your freedom.

But this makes education a tricky matter. Because the first step in education, training, or skill-building is, again, submission. Submission to communities of practice, aesthetic traditions, and the guidance of teachers and mentors.

An example: the scientist Michael Polanyi studied how knowledge was generated and applied by the sciences across different countries over time. In contrast to the positivists of the day who insisted that science could proceed rationally step by step, he advocated for the critical role of “tacit knowledge.”

This was knowledge that could not be stated explicitly, but that was passed from one scientist to the other. It included the habits, the rules of thumb, the emotions, the best practices, and the things “everyone knows” but that are hard to write down. This tacit knowledge, he argued, explained why scientific progress remained centered in Europe long after its economic dominance had faded. The culture of science had been born there, and was not easily exported.

Polanyi argued that a key feature of this tacit knowledge is that it started by submitting to authority, and learning by example:

“You follow your master because you trust his manner of doing things even when you cannot analyze and account in detail for its effectiveness.”

This idea is intolerable if, like Descartes, you believe that to be rational is to reject “example or custom” in order to “reform my own thoughts and to build upon a foundation which is completely my own.”

We are deeply wired for social learning, such that the term is virtually redundant. Every interaction with the outside world involves inhabiting and contending with the social fabric of society.

When I pick up chopsticks, it is norms that guide my fingers and shape my movements. These norms are constrained by, but not directly apparent from, the physical characteristics of the chopsticks.

When I see a wall covered in different angular shapes in slightly varying colors, I assume that it is the sunlight coming through the window creating the effect. This is partly informed by my knowledge that painters don’t usually paint walls with geometric shapes in different colors. I know the social norm that this is way too much trouble.

The opposing view to the asocial self is that individuality is something that needs to be achieved, and that others are indispensable to that effort. There is no self that exists prior to, or at a deeper level, than the self that exists in the world with others. The problem of self-knowledge is not one of introspection — it is about figuring out how we can make ourselves intelligible to others through our actions, and from them receive back a reflected view of ourselves.

Here’s the question: who are we to look to for a check on our subjective take of ourselves? Who will tell us the truth?

Crawford suggests that here, once again, skilled practices are a bridge back to reality. Skilled practices are embedded in communities of practice, aesthetic traditions, and the hard constraints of a craft, which tell us the truth far more reliably than the voices in our heads.

What it takes to be an individual is to develop a considered view of the world, and to stand behind it. Doing so exposes one to conflict, and you may have to reconsider that view.

He suggests that the act of charging money for one’s work is a prime example — you are asking for justification from another person for the work you’ve done. Pushback, negotiation, and of course, taking one’s business elsewhere are always a possibility, and that is what makes it a fair exchange. Work, then, is a mode of acting in the world that carries the possibility of justification through pay.

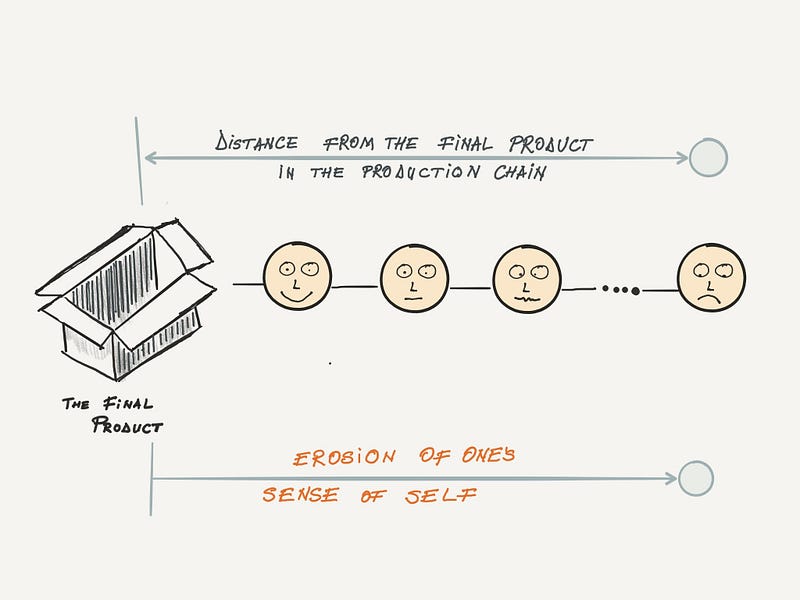

Contrast this refining process with the digital life. Once again, we insert representations between ourselves and others. What erodes our sense of self is not the narcissism of the selfie taker, but the frictionless array of weak ties in which we summon people according to our needs. The fragile self this creates is insulated from conflict, from confrontation, but is denied the interaction that would allow it to justify itself to others.

We need other people to achieve individuality. But to play that role for us, those others have to be available in an unmediated way, not via a representation tailored to our psychic comfort. And I must also make myself available to them, in an unmediated way, and face any potential conflicts.

To put this another way, for the subjectivist who thinks that what they feel or think is the ultimate test of reality, value judgments don’t actually apprehend anything. There is nothing out there in the world that could make them true or false. Your moral and aesthetic judgments can’t deepen or mature, only change. As internal states, they are basically incommunicable. Subjectivism leaves people isolated in the cocoon of their own opinions.

We don’t typically look to communities of skilled practice to refine our sense of who we are. Stripped of traditional “authoritative structures,” we look to the public. We look around to see what everyone else thinks. The demand to be an individual makes us anxious, and the remedy for this, ironically, is conformity. We become more deferential to public opinion, less willing to challenge people and institutions, further eroding the intense interaction that makes us individuals.

Thus the texture of our modern liberal society is one of polite separation. We are all equal, free, and infinitely tolerant. But we are also alone, depressed, and disconnected.

We are situated

We are told that our modern knowledge-based economy is in a state of radical flux. “Disruption” is everywhere and assumed to be good. So a twenty-first century education must form workers that are equally indeterminate and disruptable. They shouldn’t be burdened with any particular knowledge, the thinking goes. What is wanted is a generic smartness, to be applied in the abstract.

But consider what happens when you go deep into some particular skill or art. It trains your powers of concentration and perception. You become more discerning, seeing things you didn’t see before. You begin to care deeply about quality, because you have been initiated by a mentor into a spirit of craftsmanship. Your judgments mature alongside your emotional involvement, to make your knowledge truly personal.

There is always the danger of craftsmanship becoming obsessive navel-gazing. This is why it’s important that the craftsman is responsible to a wider circle of his peers. At some point he has to put his preferences aside and his cherished project on the market, and become public-spirited by financial necessity, if nothing else.

The dialectic between tradition and innovation, each begetting the other, is very different from our modern notion of creativity. We conceive of creativity as a mysterious, crypto-theological concept: something ineffable that is irrational, incommunicable, and unteachable. The skilled practitioner, by first obeying the rules of his craft, is then capable of greater feats of creative daring.

Once again, we find the paradox: to become a skilled individual first requires submission to what is. Kierkegaard taught us that rebellion is only possible from a place of reverence. A flattened human landscape, in which we are embarrassed by the idea of superiority, makes rebellion impossible. Attention to rank — the well-earned kind — can put our democratic commitments (which include rebellion) on a more firm foundation.

Conclusion

The question of what to pay attention to is the question of what to value. This question is no longer answered for us at our birth. We have to decide, each and every moment, what to attend to, which determines who we become.

In this new world, as we are free to choose our selves, we are also given a new burden of self-regulation. To gain admission to the upper-middle class and stay there, now requires nothing less than an extraordinary feat of self-discipline. The already wealthy outsource this to the professional nagging services — financial planners, tutors, personal trainers, productivity coaches — while the rest make do.

In The Weariness of the Self, Alain Ehrenberg writes that, in this new economy, the dichotomy of the forbidden and the allowed has been replaced with the axis of the possible and impossible. The question that hovers over your character is no longer how good you are, but how capable you are. Capability here is measured in something like kilowatt hours — the raw ability to make things happen.

With this shift, our primary affliction has changed. Guilt has given way to weariness. Weariness with the vague and unending project of having to become one’s fullest self.

The Latin root of the English word “attention” is tenere, which means “to make tense.” External objects provide an attachment point for the mind, a lifeline by which we can pull ourselves out of our private, virtual reality.

These external objects are delightfully concrete. They exist in well-ordered ecologies of attention. The ones described in detail in the book are those of the short-order cook, the hockey player, the motorcycle racer, the jazz musician, the glassblower, and the organ maker.

Our education taught us critical thinking and analysis, so that we could have opinions of our own. But personal development requires stepping beyond the personal — starting with submission to a world beyond your head.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Attention, Book summary, Books, Cognitive science, Flow, Personal growth, Technology, Time management