Modern digital tools make it easy to “capture” information from a wide variety of sources. We know how to snap a picture, type out some notes, record a video, or scan a document. Getting this content from the outside world into the digital world is trivial.

It’s even easier to get content that is already digital from one app to another. We know how to copy and paste text, save an image from a webpage, archive an email attachment, or import a video file.

What is difficult is not transferring content from place to place, but transferring it through time.

You know what I mean: you read a book, investing hours of mental labor in understanding the ideas it presents. You finish the book with a feeling of triumph that you’ve gained a valuable body of knowledge.

But then what?

You may try to apply the science-based methods the book recommends, only to realize it’s not quite as clear-cut as you thought. You may try to change the way you eat, exercise, communicate, or work, trusting in the power of habits. But then the everyday demands of life come rushing back, and you forget what motivated you in the first place.

At this point, people take different paths. Some give up, labeling all “self-help” books a waste of time. Others decide it’s just a problem of remembering everything they read, and invest in fancy memorization techniques. And many people become “infovores,” force-feeding themselves endless books, articles, and courses, in the hope that something will stick.

I want to suggest an alternative to all the approaches above: what you read is good and useful and very important, you’re just reading it at the wrong time.

You’re reading about time management techniques now, but they will only be useful two years from now, when you become a manager and have much greater demands on your time.

You’re watching YouTube videos on online marketing now, but that knowledge can only be put to use in 9 months, when your new online course gets off the ground.

You’re talking to a prospect about his goals and challenges now, but when you could really use that information is next year, when he is taking bids for a huge new contract.

The challenge of knowledge is not acquiring it. In our digital world, you can acquire almost any knowledge at almost any time.

The challenge is knowing which knowledge is worth acquiring. And then building a system to forward bits of it through time, to the future situation or problem or challenge where it is most applicable, and most needed.

At that future point, when you’re applying that knowledge directly to a real-world challenge, you won’t have to worry about memorizing it, integrating it, or even fully understanding it. You will only have to apply it, and any gaps in your understanding will very quickly reveal themselves. By the time you’re done solving a real problem with it, book knowledge has become experiential knowledge. And experiential knowledge is something you carry with you forever.

This is the job of a “second brain” — an external, integrated digital repository for the things you learn and the resources from which they come. It is a storage and retrieval system, packaging bits of knowledge into discrete packets that can be forwarded to various points in time to be reviewed, utilized, or deleted.

In The PARA Method, I described a universal system for organizing any kind of digital information from any source. It is a “good enough” system, maintaining notes according to their actionability (which takes just a moment to determine), instead of their meaning (which is ambiguous and depends on the context).

The four top-level categories of PARA — Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives — are designed to facilitate this process of forwarding knowledge through time.

- By placing a note in a project folder, you are essentially scheduling it for review on the short time horizon of an individual project

- Notes in area folders are scheduled for less frequent review, whenever you evaluate that area of your work or life

- Notes in resource folders stand ready for review if and when you decide to take action on that topic

- And notes in archive folders are in “cold storage,” available if needed but not scheduled for review at any particular time

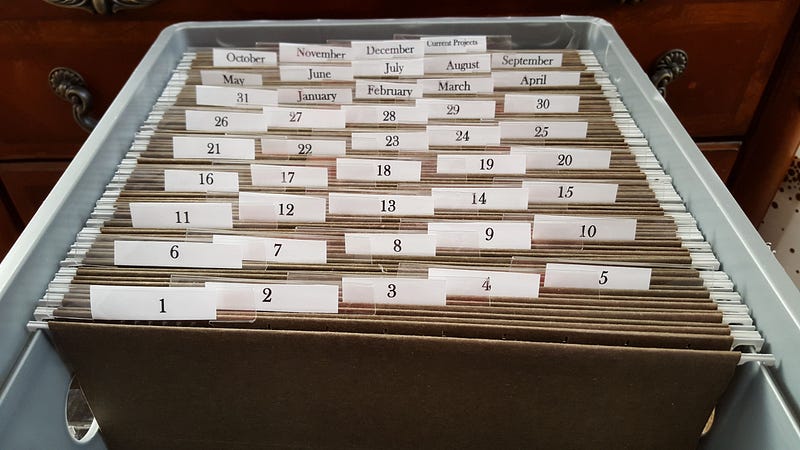

Note that we have re-created the tickler file, except instead of strict time-based horizons (daily, weekly, monthly, annually), they are scheduled contingently — if X happens, when Y arrives, if I want to do Z, etc.

Planning in terms of contingencies gives us all the benefits of planning and researching, without locking us into rigid routines. We have the ability to massively accelerate, using our repository of accumulated notes as rocket fuel. But the actual decision of whether or not to accelerate, and critically, in which direction, we leave to our Future Self, who is older and wiser.

PARA answers how these “packets of knowledge” are organized: in discrete notes, sorted into 4 categories according to actionability, and resurfaced using RandomNote.

But now we turn to a more fundamental question: how are these packets made? Once we capture something, how do we structure the note so that it’s easily discoverable and usable in the future? How do we make sure what we’re saving today adds value to future projects, even when we can’t predict or even imagine what those projects might be?

That is the job of Progressive Summarization.

Note-first knowledge management

There are two primary schools of thought on how to organize a note-taking program (or really any body of information, but I’ll use terms specific to note-taking apps):

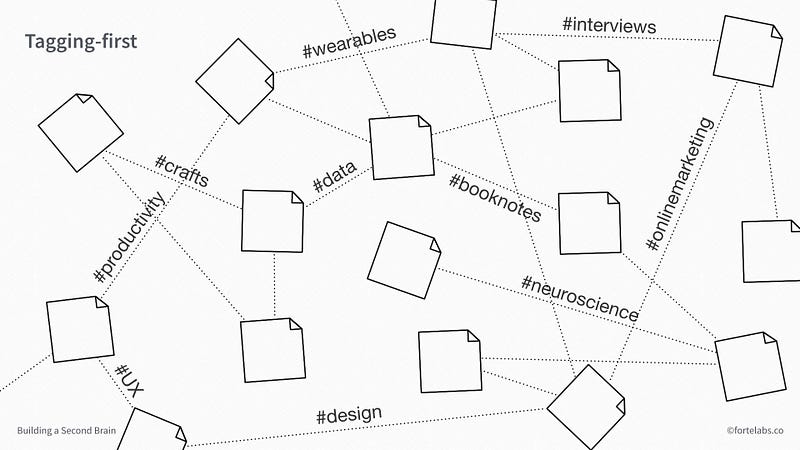

Tagging-first approaches argue that there should be no explicit hierarchy of notes, notebooks, and stacks. Notes are envisioned as an ever-changing, virtual matrix of interconnected, free-floating ideas. Because many tags can be applied to one note, there are multiple pathways to discover any given note. Locating notes in specific notebooks and folders is seen as limiting and static.

Although tags have their uses, I don’t believe they work as a primary organizational system. In my experience, relying on tagging is too fragile and requires too much maintenance, spreading attention too uniformly across all notes whether or not they are truly valuable. The virtual matrix sounds cool and futuristic, but our minds are not made to work well with such abstract concepts — we understand placing one thing in one place intuitively and automatically.

The second conventional approach to organizing notes is notebook-first. This basically translates how we organize things in the physical world — in a series of discrete containers — into the digital world.

Notebook-first is better than tagging-first, in my opinion, mostly because it stays out of the way. It doesn’t try to automate and encroach upon the deeply intuitive act of making connections and seeing patterns. PARA on its own is a notebook-first system.

But if we stopped there, it would still be woefully inadequate for an economy based on creative output. As the tagging enthusiasts correctly point out, notebooks and folders actually suppress the serendipity and randomness that is at the heart of a creative lifestyle.

I propose a way to break the impasse: a note-first approach.

I propose we make the design of individual notes the primary factor, instead of tags or notebooks. This has many advantages:

- It works well with any other organizational system, without depending on them (including but not limited to tags and notebooks, if you want to use those)

- It makes all work you do on your notes value-added, because you’re spending close to 100% of the time engaging directly with the content itself

- It can more easily survive migrations to other devices, storage locations, and even programs, because note content is much more likely to be preserved than overarching structure

- It cultivates skills (succinct communication, finding the core of an idea, visual thinking, etc.) that are inherently valuable and highly transferrable to other activities

- It makes your notes more legible and useful to others (unlike your internal notebook structure, which is only for your use), promoting collaboration and sharing

With a note-first approach, your notes become like individual atoms — each with its own unique properties, but ready to be assembled into elements, molecules, and compounds that are far more powerful.

Designing discoverable notes

A note-first approach to knowledge management means we have to think about design. You are, in a very real sense, designing a product for a demanding customer — Future You.

Future You doesn’t necessarily trust that everything Past You put into your notes is valuable. Future You is impatient and skeptical, demanding proof upfront that the time they spend reviewing notes will be worthwhile. You’ve gotta “sell them” on the idea of reviewing a given note, including all the stages any salesperson has to master: gaining attention, inspiring interest, establishing credibility, stoking desire, and making a case for action NOW.

As if all that wasn’t intimidating enough, you have to do this for every single note without spending any extra time. You don’t have extra time, do you?

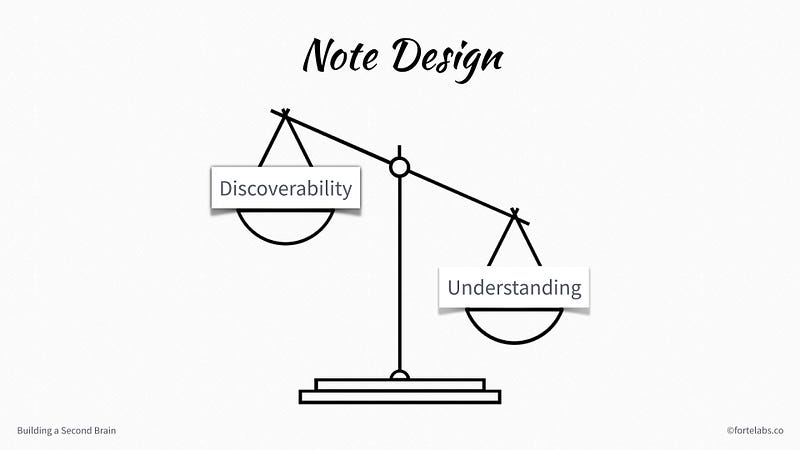

Let’s start at the beginning: at the heart of every design, we are trying to balance priorities. You want one thing, but it has to be balanced against something else that you also want.

You want a vehicle to protect its occupants, but you can’t just add layers and layers of titanium armor plating. You have to balance safety against weight and cost.

You want a phone to have the longest possible battery life, but you can’t just give it a 10-pound brick of a battery. You have to balance battery life against size and usability.

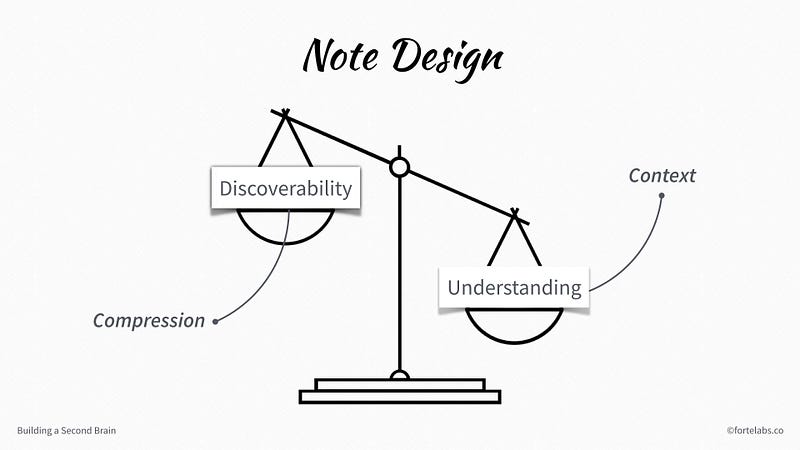

In the case of notes, I believe the two priorities we are trying to balance are discoverability and understanding.

Making a note discoverable involves making it small, simple, and easy to digest. We accomplish this using compression: creating highly condensed summaries, without all the fluff.

But we also want to make our notes understandable. This involves including all the context: the details, the examples, and cited sources to be sure nothing falls through the cracks.

This is a difficult tradeoff because you cannot compress something without losing some of its context.

You cannot summarize an article without discarding most of its points. You cannot make a highlight reel of a video without cutting out most of the footage. You cannot give an 18-minute TED talk without leaving out most of your ideas.

In making decisions about what to keep, you are inevitably making decisions about what to throw away.

Compression vs. context

There’s a natural tension between the two, compression and context.

To communicate anything, you have to compress it, like communicating a huge amount of life experience in a wise saying. But in doing so, you lose a lot of the context that made that wisdom valuable in the first place.

Let’s look at some examples.

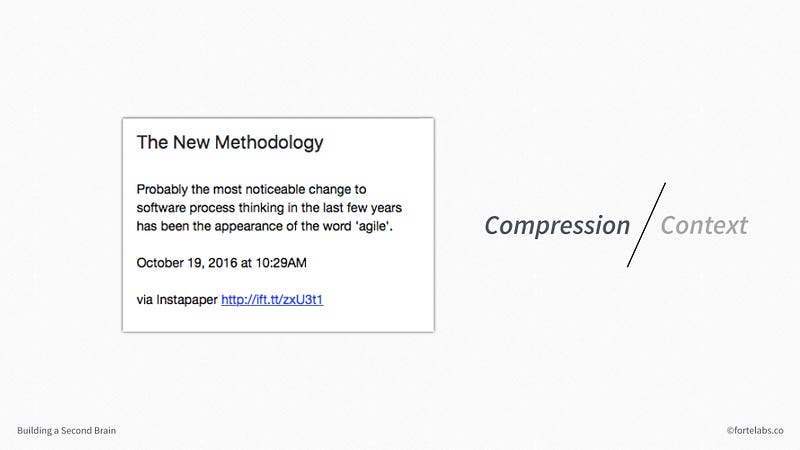

If we compress a note too much, in other words, we make a summary that is too brief, we lose the context and it loses all meaning. In the note above, for example, the information it contains is highly discoverable — I can get the gist of it with just a glance.

But if I come across this note a year from now, I’ll have no idea what it means or why it’s important. It’s too compressed.

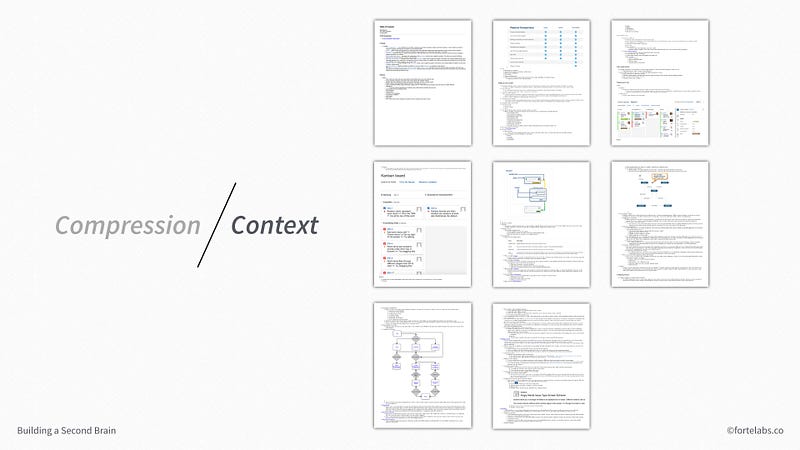

But we can go too far in the opposite direction too. If we make something totally understandable, in other words, if we include every little detail and bit of context, it loses its discoverability.

The example above is my notes on the task management software Jira. It has lots of context, making it highly understandable. But it’s not discoverable at all. It would probably take me a couple hours and tremendous mental effort to read through this note and remember enough context to decide whether or not it’s useful. The main points and key insights are hidden somewhere in the noise.

Getting the balance between compression and context right is not a trivial matter. When the time comes for Future You to decide whether or not to review this note, seconds count. Because Future You will likely be looking for a solution to a problem, not casual reading, they will be making snap decisions on a tight timeline. Faced with a wall of text of questionable value, they are unlikely to take the risk of committing time for review.

This means that all the summarizing work your Past Self did on this note is wasted. It didn’t pay off back then, and it doesn’t pay off in the future. You successfully sent a packet of information forward through time, but not in a state where it could survive the journey.

Opportunistic compression

I’ve found that most people do just fine on the context side of the equation. We know how to take exhaustive notes on a book, a presentation, or a class.

Progressive Summarization focuses therefore on rebalancing the equation. It is a method for opportunistic compression — summarizing and condensing a piece of information in small spurts, spread across time, in the course of other work, and only doing as much or as little as the information deserves.

If you remember, compression is a means to improving discoverability. So our design challenge when creating a note is:

“How do I make what I’m consuming right now easily discoverable for my future self?”

This isn’t an easy question to answer, because you have no idea what Future You remembers, is interested in, or is working on. You have to summarize the note without knowing what it will be used for. It is general purpose summarization, a much greater challenge than extracting takeaways for just one specific project.

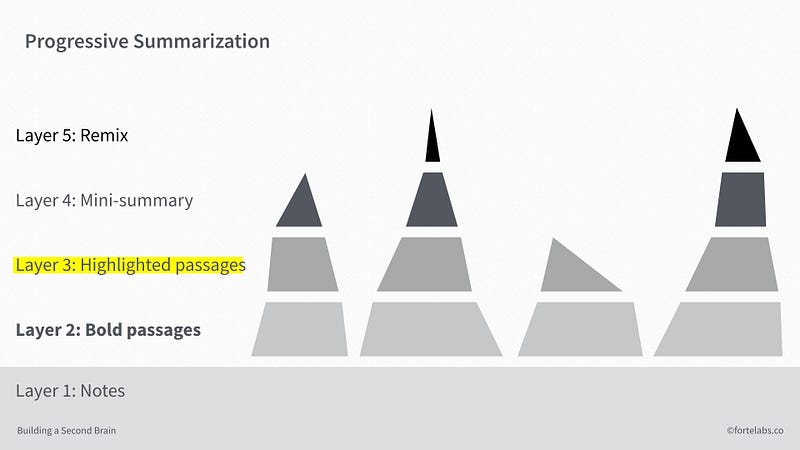

Progressive Summarization works in “layers” of summarization. Layer 0 is the original, full-length source text.

Layer 1 is the content that I initially bring into my note-taking program. I don’t have an explicit set of criteria on what to keep. I just capture anything that feels insightful, interesting, or useful.

This can include virtually any type of media, but for this article I will focus on text. There are many ways of doing this:

- Copy a paragraph of text from a PDF I’m reading, and paste it into the Evernote menu bar helper

- Type my random thoughts into a new note on the Evernote mobile app

- Dropping a Word document onto the Evernote icon in the dock on my Mac, which adds it to a note as an attachment

- Downloading all my Kindle highlights from a book using Bookcision, and then copying and pasting them into a new note

- Forward an email with useful information to my personal import address, which automatically imports the whole email to a note

- Highlight the best passages of an online article using the web highlighter Liner, which exports directly to Evernote

The examples above are from my recommended program Evernote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, browsers), but all the major note-taking platforms support the above functionality in one way or another: Bear (Mac and iOS), Simplenote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, Linux), Microsoft OneNote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows), and Google Keep (browsers, iOS, Android).

Layer 1 is the starting point of Progressive Summarization, like the bedrock on which everything else is built:

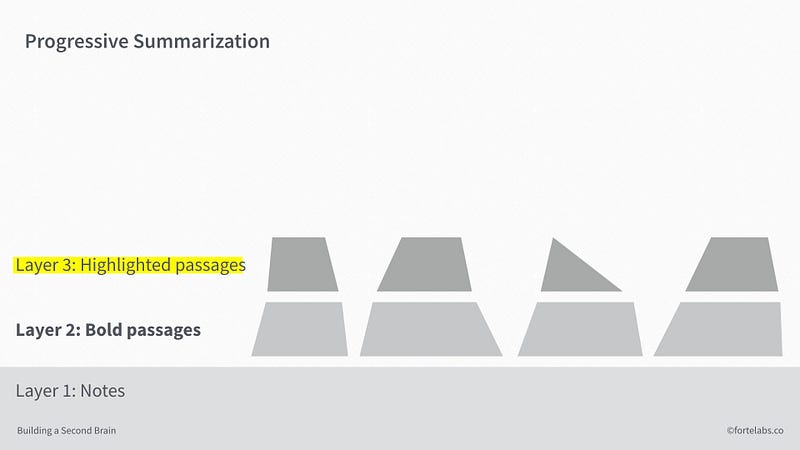

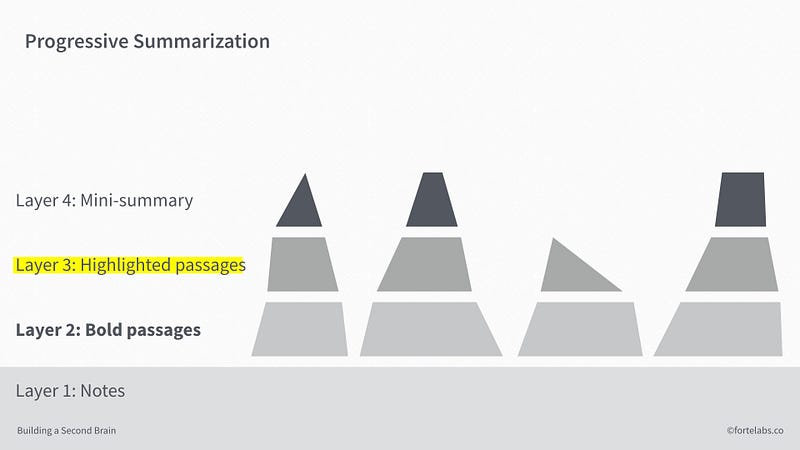

Layer 2 is the first round of true summarization, in which I bold only the best parts of the passages I’ve imported. Again, I have no explicit criteria. I look for keywords, key phrases, and key sentences that I feel represent the core or essence of the idea being discussed.

I do this bolding layer at a later time, when I’m already reviewing this note anyway. I’m essentially using the attention I’m already spending for a dual purpose: to “buy” the information I need for the project at hand, and also to summarize the note for future use. If you have to pay attention to something, it comes in handy to be able to double-spend.

For Layer 3, I switch to highlighting, so I can make out the smaller number of highlighted passages among all the bolded ones. This time, I’m looking for the “best of the best,” only highlighting something if it is truly unique or valuable. And again, I’m only adding this third layer when I’m already reviewing the note anyway.

For Layer 4, I’m still summarizing, but going beyond highlighting the words of others, to recording my own. For a small number of notes that are the most insightful, I summarize layers 2 and 3 in an informal executive summary at the top of the note, restating the key points in my own words.

Note that all the previous layers are preserved in context, giving you the freedom to leave things out without worrying that you’ll lose them. Summarization is risky — you may be making the wrong decision about what’s important. But with the safety net of multiple layers of preserved notes, you can strike out decisively on daring intellectual expeditions.

And finally, for a tiny minority of sources, the ones that are so powerful and exciting I want them to become part of how I think and work immediately, I remix them. After pulling them apart and dissecting them from every angle in layers 1–4, I add my own personality and creativity and turn them into something else.

This could include a blog post interpreting, critiquing, or extending the argument an author is making, such as in Strategically Constrained, The Inner Game of Work, and Supersizing the Mind.

But it doesn’t have to be difficult or time-consuming. It could even be…(gasp) fun! Making a sketch, designing a slide, recording a short video on your phone, and sharing on social media are all forms of wrestling deeply with information.

1/ In many ways, we understand less about Toyota’s success than ever, despite it being one of the most studied companies in history

— Tiago Forte (@fortelabs) November 16, 2016

In Part II, we’ll look at some examples of Progressive Summarization in action.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Attention, Building a Second Brain, Curation, Flow, How-To Guides, Note-taking, Workflow